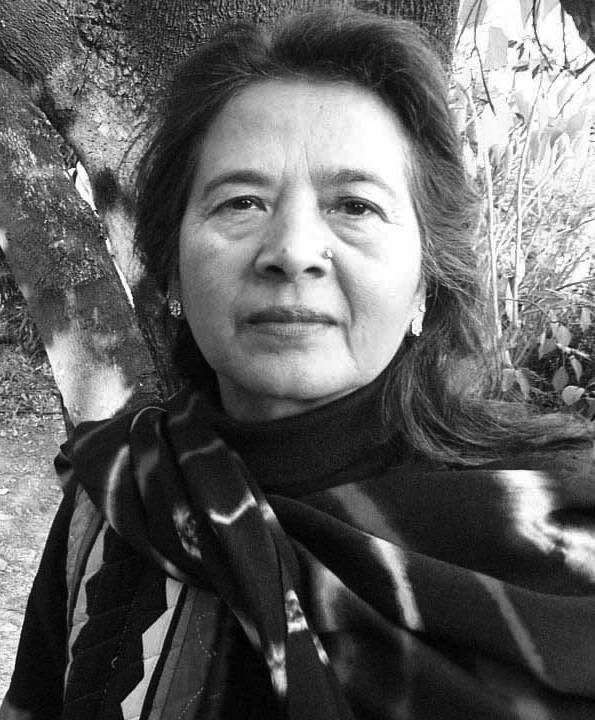

Banira Giri was born in Kurseong near Darjeeling in West Bengal. She became the first Nepali woman to be awarded a PhD from Tribhuvan University, for her work on the revolutionary Nepali poet, Gopalprasad Rimal. The force and intention of his anti-establishment voice animates much of her own writing. Giri is one of the very few Nepali women writers to have established a reputation outside Nepal.

"Poetry is my first love; it is my most personal urge," writes Giri. "If someone wanted to punish me, forbidding me to write would be a far greater punishment than sending me to jail. The spirit that drives my poetry emerged from hearing my mother recite Sanskrit and Nepali shlokas in her morning puja. Directly or indirectly she prepared the ground for my poetic consciousness – whatever creative powers I have first sprouted in my earliest childhood.

"My father played his part as well. During the cruel period of Rana rule, he traveled from east Nepal on a tiresome journey to settle in the small Indian town of Kurseong. There he started a small roadside business selling cloth – more a kind of meditation than business. He'd ask whoever came from Nepal about the political unrest there. His queries and stories about the revolutionaries, the martyrs, became the foundation of my political consciousness. And I was brought up on the Nepali books and journals he brought into the house – Bal Krishna Sama, Devkota and Rimal. Whatever he earned he sent back to the village, but though he wanted to, he never returned. I can also say that the earthly and spiritual beauty of Nepal – its wide and varied landscape and views, its heights and depths, shaped my poetry. Most of my poems express love for this country, my life and its surroundings.

"Without spontaneity what is the point of writing poetry? In 'The Chant Freedom!' the lines came spontaneously, quickly and honestly. This stream of language has meaning, sound and depth and overall expresses the very sympathy of my heart. Many of my poems came to me in this way. But my poems are not just personal expression; they are forged in the workshop of political and social sensitivity. If one thinks the poem 'Wound' is about a part of the human body or is bound to a particular incident, this is absolutely wrong. The poem is rather concerned with willful violations of the innocent and powerless by the powerful. All my poems have ideas in play and it is up to the reader to recognize them. In whatever way the poem is read or interpreted, the language, the way of writing and the honest intent of the poet is what makes the writing poetry.

"In 'Pashugayatri' I emphasize the eternal relationship of humans with nature, the environment and the universe. The sacred verses of the Rig Veda read for a dying person reverberate here, as do the intonations of my mother's voice. If the poem is read well, the concern for the death of the Bagmati River is also concern for the environment at large, the fate of the earth in this age of environmental degradation. We are all connected to life and nature. Poetry celebrates this connection. It also raises a warning voice to those who would ignore and violate all that is human and natural. To ignore the call of the earth, to violate our human connection to ourselves and to our surroundings – is that not also to strike a blow against poetry, against inspiration? The poet will always raise his voice against this desecration."

NaN