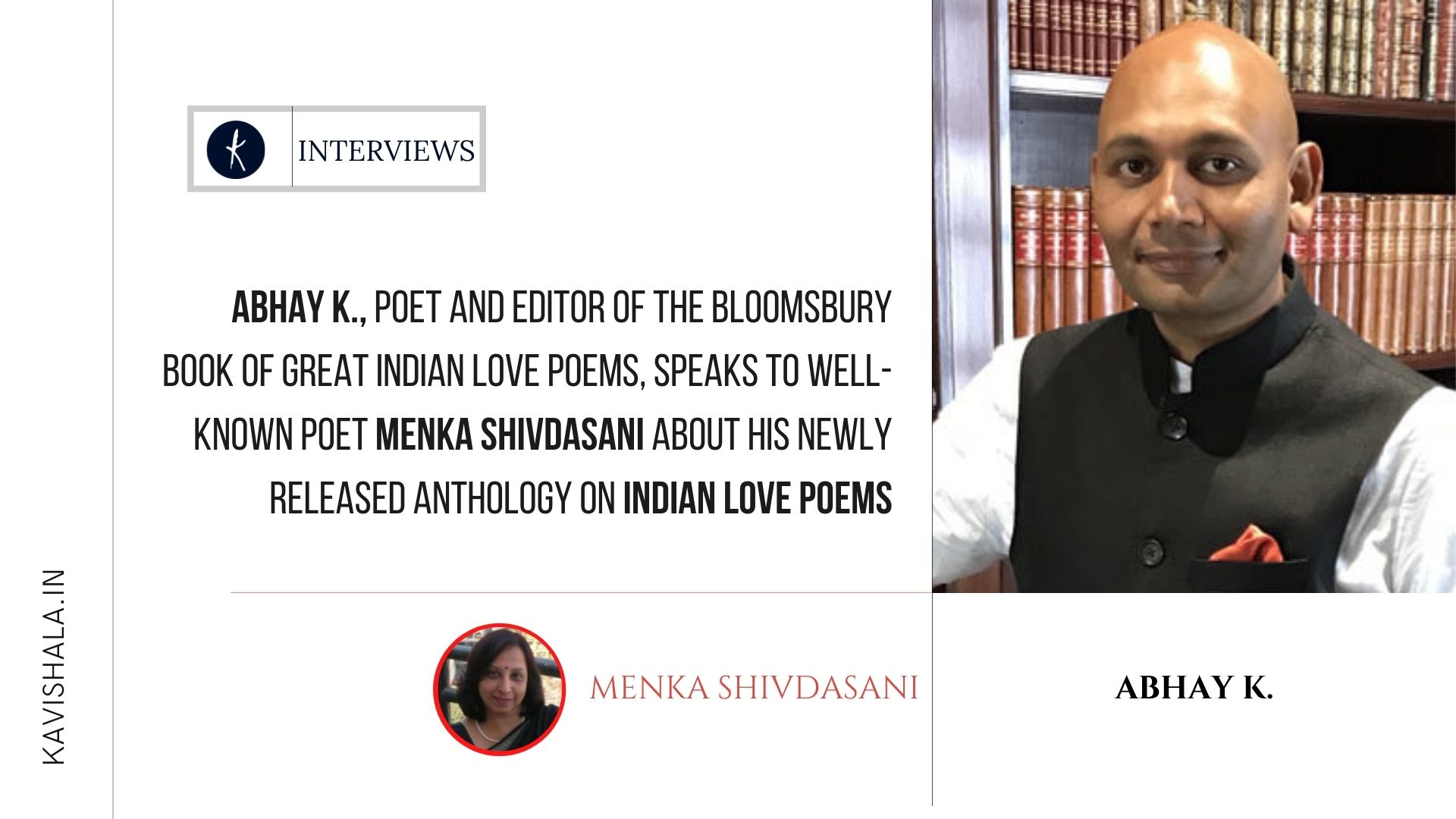

Abhay K., poet and editor of The Bloomsbury Book of Great Indian Love Poems, speaks to well-known poet Menka Shivdasani

Menka Shivdasani: Love is a theme that many writers and anthologists have explored over the decades. There was Meena Alexander’s Indian Love Poems, for example, in 2005, which featured work from across more than two- and- a- half millennia, from classical languages such as Sanskrit and Tamil, and later languages like Hindi, Urdu, Malayalam, Bengali and English – from the 12th century to contemporary times. In fact, in your Editors’ Note, you name many of these works. When you decided to edit an anthology of Great Indian Love Poems, what were you hoping to do that would be different, and what made you think the time was right for such a collection?

Abhay K.: The idea to edit an anthology of Indian Love Poems came while I was editing The Bloomsbury Anthology of Great Indian Poems covering 28 Indian poems spanning over 3000 years of Indian poetry as many of these great Indian poems were love poems. Love is an emotion that each one of us feels and experiences. Love is fundamental to human existence. Therefore, I decided to put together an anthology of Indian love poems during the pandemic last year while everyone was busy writing poems on COVID-19 pandemic or editing anthologies related to it.

While reading Meena Alexander’s Indian Love Poems and other anthologies on Indian love poetry published earlier, I felt that love poems from more Indian languages needed to be included. I also felt that fresh translations of many well-known Indian love poems were needed, as well the new voices from the younger generation of Indian poets needed to be given space. The COVID-19 Pandemic made us even more aware of the need to express love for our near and dear ones and spend time with them. Therefore, there could not have been a more appropriate time to publish this anthology.

Menka Shivdasani: In your Editor’s Note, you speak of six varieties of love, as described in ancient Greek philosophy. What were these different forms of love, and do you think the poems you received did justice to them all? Would you say any of these varieties particularly informs or influences poems by Indian writers? What makes Indian love poems unique from those written in other civilisations?

Abhay K.: Six varieties of love described in ancient Greek philosophy are: eros (sexual passion), phila (platonic love), ludus (playful affection), pragma (mature love), agape (selfless love) and philautia (self-love). I think poems included in this anthology express all these varieties of love, although some varieties are more represented than the others. Many of the early love poems written in Sanskrit and Prakrit express mostly eros and ludus, while the more recent Indian love poems express phila, pragma, agape and philautia.

The coming together of devotional and sensual love is one of the key dimensions of Indian love poetry, where they become inseparable from each other. Look at these lines –

You’re one with me, apart too

How to describe you

You’re beloved, God too

How to describe you

— Sachal Sarmast

I am on fire

with heartfelt desires.

Lord,

cut through the greed in my heart,

show your way

out

Lord, white as jasmine.

— Akka Mahadevi

The indispensability of nature in Indian love poetry also makes it unique. Even flowers, plants, animal, seasons, rain, rainbow, wind, sun, moon, stars, stones, rivers, mountains among other things animate and inanimate have their own sensual personas and feature prominently in Indian love poetry. Kalidasa’s Meghaduta mentions 26 different kinds of plants and flowers such as Mango, Ashoka, Rodhra, various species of Jasmine, Kakubha, Kurbaka, Mandara, among others.

Menka Shivdasani: From Sumerian cuneiform tablets to ancient Arab and Persian poetry, and Maya and Inca civilisations and elsewhere – love is a universal theme that spans all cultures. As you explored the rich traditions of Indian poetry from 28 languages over 3000 years, what elements did you find most striking? What were the themes that came across most forcefully to you?

Abhay K.: I think it is the constant struggle between sensuality and spirituality in Indian poetry and philosophy that strikes me the most. Here is a poem by poet-monk Dharmakirti, who taught at Nalanda University, that sums this unending tug of war –

Making love to her lasts only moments

like a dream, illusion, ending in regret

I reflect upon this truth a hundred times

Yet my heart can’t forget the gazelle-eyed girl.

— Dharmakirti

In Indian philosophy, pursuit of Kama (enjoyment) is an essential step along with Dharma (right conduct) and Artha (economic prosperity) in obtaining Moksha (ultimate liberation / self-actualisation).

Vatsayayana’s Kamasutra defines Kama as follows – “Kama is the enjoyment of appropriate objects by the five senses of hearing, feeling, seeing, tasting, and smelling, assisted by the mind together with the soul. The ingredient in this is a peculiar contact between the organ of sense and its object, and the consciousness